One Month Out of Every 48 Ritual When Did the Olypics Start Again

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/e3/d0e31881-a25d-4141-a115-94fe092ade2a/britannia-olympics-631.jpeg)

What is known as Wenlock Edge, a nifty palisade, almost 1,000 feet high, running for 15 miles through the canton of Shropshire, overlooks, virtually its eastern end, the tidy town of Much Wenlock. (Much Wenlock existence and so named, you see, to distinguish it from its even wee-er neighbor, Little Wenlock.) Notwithstanding, to this quaint backwater village near Wales came, in 1994, Juan Antonio Samaranch of Espana, the grandiose president of the International Olympic Committee.

Samaranch, an old spear carrier for Franco, was a vainglorious corporate pol, either obsequious or imperious, depending on the company, who was never much given to generosity. Yet he found his way to Much Wenlock, where he trooped out to the cemetery at Holy Trinity Church and placed a wreath on a grave in that location. Samaranch and so declared that the man who lay at his feet beneath the Shropshire sod "really was the founder of the modern Olympic Games."

That fellow was affectionately known as Penny Brookes; more formally, he was Dr. William Penny Brookes, the most renowned citizen of Much Wenlock—at least since the eighth century, when the prioress of the abbey there, St. Milburga, regularly worked miracles (notably with birds she could order virtually), while also displaying a singular power to levitate herself. If not quite and then spectacular every bit the enchanted prioress, Penny Brookes was certainly a man of upshot—fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, town magistrate and founder of the National Olympian Association in 1865—which, significantly, he created years before the International Olympic Committee was formed. Even so, however Samaranch's homage, Brookes and his lilliputian boondocks are seldom cited in Olympic liturgy.

Olympic myth runs rife, too, generously embroidered with Pollyanna. Most peculiarly, from its inception, modern Olympic advocates take trumpeted that their sweaty contests are much more uplifting—a noble "movement" of brotherhood that will somehow influence u.s.a. grubby mortals to stop our mutual carping and warring. Alas, poetry and peace ever then wing off with the doves.

Also gospel is it that a Frenchman, venerating Greek antiquity, cowered by German physicality, was the initiating forcefulness behind the re-creation of the Games. But that'southward only truthful so far every bit it goes. The fact is that the modern Olympics owe their birth and their model and, ultimately, their success foremost to England. For that matter, as nosotros shall see, the kickoff London Games, those of 1908, which were fashioned out of whole fabric by a towering Edwardian named Willie Grenfell—or Lord Desborough, as he had become—essentially saved the Olympics as an institution. It's really quite advisable that, in a few weeks hence, London volition become the first urban center since Olympia to host the Games 3 times.

Across the aqueduct, Pierre Frédy was born in Paris in 1863 into the French elite. He grew up as an unapologetic chauvinist, but notwithstanding, even as France declined as a earth presence, nothing ate at immature Pierre more than the fact that Germany had whipped French republic in the Franco-Prussian State of war when he had been but an impressionable tot of vii. Pierre became convinced that a considerable reason for France's shellacking was that the German language soldiers had been in much better shape.

This was certainly true, too, as young Germans were assembled to participate in turnen, which were tedious, rote physical exercises that, like eating your spinach, were good for y'all. Only Pierre Frédy's antipathy for anything Teutonic inhibited him from simply encouraging French leaders to have their youth ape their victors' concrete education. Rather, by adventure, he happened to read the British novel Tom Brown's School Days, and thereupon Pierre, who would arise to the title of the Businesswoman de Coubertin, had what could just be described every bit a spiritual experience.

Tom Brownish's was about a smallish boy who goes off to boarding school at Rugby, where he participates in the schoolhouse's athletics, which helps him to thrash the big smashing, Flashman. Moreover, the climax of the novel is a game—a cricket friction match. The young baron was hooked. Non but did he want to improve the physical condition of his ain countrymen by emphasizing the British way of sport, merely he began to conjure up the greater dream of reinstituting the ancient Greek Olympics, thereby to ameliorate the whole globe.

The original Olympics had been banned in A.D. 393 past the Roman emperor Theodosius I, just despite the prohibition, Europeans of the Nighttime and Middle ages kept playing their games. Frivolity by the lower classes is, nonetheless, not the stuff of history, saved. Rather, nosotros mostly but have glamorous tapestried depictions of the nobility occupied at their expensive blood sports.

Nosotros exercise know, though, that by the 11th century in Scotland, various tournaments of force were held. These were the aboriginal forerunners of what became the Highland Games, but information technology was not until 1612, further south in England, that the embryonic modern Olympics first made their appearance. This was an athletic festival that was held on the estate of i Capt. Robert Dover, and it included the likes of fencing and "leaping" and wrestling, "while the young women were dancing to the tune of a shepard'due south [sic] pipe." It was fifty-fifty known, in fact, as the Cotswold Olympick Games. Captain Dover was a Roman Catholic, and he devilishly scheduled his festival as a joyous in-your-face exhibition to counter the dour Puritanism of the time. Unfortunately, with his death in 1641 the annual able-bodied celebration petered out.

The idea of replicating the ancient Olympics had taken on a certain romantic appeal, though, and other English towns copied the Cotswold Olympicks on a smaller scale. Elsewhere, too, the idea was in the air. The Jeux Olympiques Scandinaves were held in Sweden in 1834 and '36; and the then-called Zappas Olympics in 1859 and '70 were popular successes in Greece. Still, when a butcher and laborer won events in 1870, the Athenian upper classes took umbrage, banned hoi polloi, and subsequent Zappas Olympics were but sporting cotillions for the elite. For the first time, amateurism had reared its snotty head.

Ah, but in Much Wenlock, the Olympic spirit thrived, year subsequently year—as information technology does to this day. Penny Brookes had beginning scheduled the games on October 22, 1850, in an effort "to promote the moral, physical and intellectual comeback of the inhabitants" of Wenlock. However, notwithstanding this loftier-minded purpose, and unlike the sanctimonious claptrap that suffocates the Games today, Penny Brookes also knew how to put a smiling on the Olympic face. His annual Much Wenlock games had the breezy ambient of a medieval county off-white. The parade to the "Olympian Fields" began, accordingly, at the ii taverns in boondocks, accompanied by heralds and bands, with children singing, gaily tossing blossom petals. The winners were crowned with laurel wreaths, laid on past the begowned fairest of Much Wenlock'due south off-white maids. Besides the classic Greek fare, the competitions themselves tended to the eclectic. I year there was a blindfolded wheelbarrow race, another offered "an quondam adult female's race for a pound of tea" and on yet another occasion in that location was a grunter hunt, with the intrepid swine squealing past the town's limestone cottages until cornered "in the cellar of Mr. Blakeway'due south house."

If all this sounds more like a children's birthday party, Penny Brookes' games could exist serious business organization. Competitors traveled all the way from London, and, flattered that Brookes had so honored his noble heritage, the king of Greece, in faraway Athens, donated a silver urn that was awarded each year to the pentathlon winner. The renown of Shropshire'due south sporting competition under the cusp of the Wenlock Edge grew.

It is of particular historical interest that fifty-fifty from the inaugural Much Wenlock games, cricket and football were included. The Greeks had never tolerated any ball games in the Olympics, and likewise the Romans dismissed such activity as child'southward play. Although English monarchs themselves played court lawn tennis, several kings issued decrees banning brawl games. The fear was that the yeomen who amused themselves and so, monkeying around with balls, would non be dutifully practicing their archery in grooming for fighting for the Crown. Even as the gentry migrated to the New World, it continued to disparage brawl games in comparing with the barbarous butchery of the hunt. Thomas Jefferson was moved to say: "Games played with the brawl . . . are likewise violent for the torso and postage no character on the mind." Talk well-nigh over-the-top; yous would've thought Alexander Hamilton was playing shortstop for the Yankees.

Simply as the 19th century moved forth, ball games throughout the English language-speaking world of a sudden took on acceptance. Cricket, rugby, field hockey and football in United kingdom; baseball and American football in the United States; lacrosse and ice hockey in Canada; Australian rules football down nether—all were codified within a relatively short period. Sorry, the Duke of Wellington never did say that Waterloo was won on the playing fields at Eton, but it was true, specially in upper-chaff schools like Eton and Rugby, as at Oxford and Cambridge, that team games began to proceeds institutional approval. As early on as 1871 England met Scotland in a soccer match in Edinburgh.

De Coubertin was beguiled by this English language devotion to sport. Himself a little beau (see Brown, Tom), invariably put out in a frock coat, the baron was, however, utterly naked of either amuse or sense of humor. Rather, he was distinguished past a flowing mustache that was a thing of majesty and affectation. However those who personally encountered him were virtually entranced by his dark piercing eyes that lasered out beneath heavy eyebrows. Like his eyes, the baron was full-bodied of heed. He was unswerving, and his resolution showed. When he met Theodore Roosevelt, the smashing president felt obliged to declare that he had finally actually encountered a Frenchman who was not a "mollycoddle."

Richard D. Mandell, the premier Olympic historian, has written that de Coubertin sought out fellows of his own wealthy, classically trained bourgeois ilk—"most were congenial, well-meaning second-rank intellectuals, academicians and bureaucrats." Still, few of them bought into de Coubertin'south Olympic dream. For that thing, some plant it absolutely screwball. All the same, the baron was indefatigable; in today's world he would have been a lobbyist. He was forever establishing shadow committees with impressive letterheads and setting up meetings or higher falutin gatherings he billed as "congresses." Apparently, he always traveled with a knife and fork, constantly property forth over dinners, entertaining, pitching...well, preaching. "For me," he declared, "sport is a organized religion with church, dogma, ritual." Ultimately, his obsession with Olympism would cost him his fortune and the love of his embittered wife, and at the end, in 1937, his centre would, appropriately, be buried in the beloved past, in Olympia.

But for his present he inhabited the soul of England. He journeyed across La Manche, and with his connections and facility for name-dropping, he fabricated all the correct rounds. Even better, there was the glorious pilgrimage to Rugby, to bond with the fictional Tom Brownish, to grow even more enamored of the English language athletic model. Ironically, likewise, that was really something of a Potemkin arena, considering dissimilar the High german masses at their boring exercises, it was only the British upper classes who could afford the time for fun and games. After all, the "lower orders" could inappreciably be trusted to act upon the field of play in a proper sportsmanlike way. The original British definition of apprentice did non only mean someone who played at sport without remuneration; rather, it was much broader: An amateur could merely be someone who did non labor with his hands. When the Crown began mustering its youth to serve in the Boer War, information technology discovered that large numbers of Englishmen were in poor concrete status. De Coubertin, though, ignored the bodily for the ideal.

In 1890, he journeyed to Much Wenlock, dining there with Penny Brookes. For possibly the starting time time, the baron was not required to proselytize; good grief, he was a downright Johnny-come-lately. Why, it had been a decade since Penny Brookes had offset proposed that not only should the Olympics be reinstituted, but they should exist held in Athens. Talk nigh preaching to the choir. One can patently see the immature Frenchman beaming, twirling that fantastic mustache, every bit the erstwhile doctor told him how "the moral influence of physical culture" could actually ameliorate the whole damn earth.

Then de Coubertin hied to the Olympian Fields and saw the Games for real. Aye, it was only Much Wenlock, one little town in the Midlands, and the Olympians were more often than not simply Shropshire lads, but now it wasn't a dream. Right earlier his eyes, the baron could see athletes running and jumping, with laurel wreaths placed upon the victors' brows and brotherhood upon the horizon of sport.

Alas, Penny Brookes died in 1895, the year earlier de Coubertin had persuaded the Greeks to hold the offset modern Olympics. Those Games were popular in Athens, as well, but little attention was paid them elsewhere. Despite all his schmoozing in England, the baron hadn't been able to break into the Oxford-Cambridge inner circumvolve, and simply six British athletes entered the lists at Athens. Moreover, when two servants working at the British Diplomatic mission registered for a wheel race, English gild actually looked down its noses at this Much Wenlock knockoff. There goes the neighborhood.

The Greeks urged de Coubertin to make Athens the perennial Olympic home, but he foresaw, correctly, that the Games needed to exist a roadshow to gain any sort of global foothold. But beware what y'all wish for; the next two Olympics were nothing curt of disaster. First, as a prophet without award in his native land, de Coubertin could only go Paris to have the 1900 Games as office of its world's fair, the Exposition Universelle Internationale. The events were scattered over v months and were barely recognized as a detached tournament. Included was a competition for firemen putting out a bonfire, ballooning and obstacle pond races.

If information technology is possible, though, the subsequent '04 Games in St. Louis were even more a travesty. Again, the Olympics were subsumed by a world's carnival—the Louisiana Purchase Exposition; "come across me in St. Loo-ee, Loo-ee, run across me at the fair"—and near the only competitors to evidence up were homebred Americans. Mud fighting and climbing a greased pole were highlighted Olympic events. Three strikes and de Coubertin would've been out after 1908, so he reached back into Classical history and bet information technology all on the Eternal Urban center. Explained he at his oracular best: "I desired Rome just because I wanted Olympism, after its render from the excursion [italics mine] to utilitarian America, to don over again the sumptuous toga, woven of art and philosophy, in which I had always wanted to clothe her." In other words: SOS.

But the Italians began to go cold feet after they heard virtually the Missouri farce, and when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 1906, they used the disaster as an alibi to beg off. The baron had merely one card left to play, only, mercifully, all the years of kissing up to the Brits paid off. On November 19, 1906, London accepted the challenge to host the IVth Olympiad, which would open in July of 1908, only 19 months hence. There was no stadium, no plans—non much of anything but Lord Desborough, the intrepid Willie Grenfell, knight of the Lodge of the Garter, member of Parliament, squire of stupendous Taplow Courtroom—a man who had climbed the Matterhorn, swum the Niagara rapids and rowed beyond the Channel. Now he volunteered to have charge of the floundering Olympics.

At half dozen-foot-5, Lord Desborough was a giant for that time. If he didn't know everyone worth knowing, his wife did. Ettie, Lady Desborough, was the queen bee of what was described as "The Souls" of London social club, entertaining at Taplow in an arc from Oscar Wilde to the Prince of Wales to Winston Churchill. Ettie'south biographer, Richard Davenport-Hines, besides describes her as at once a prude and an outrageous flirt (adulteress?), especially with gorgeous younger men who were referred to every bit her "spangles." Her favorite word was "golden."

And why not? In 1906, when Lord Desborough took on the rush chore to salvage the Olympics, Ettie was at the height of her social powers and her beautiful children—Julian and Baton and the girls—were curly-haired, blond angel dolls, equally was their London notwithstanding the largest and most influential city in the earth. Britannia ruled the waves. And Lady Desborough had the time for her soirees and her spangles because her married man was invariably otherwise occupied. Information technology was said that in one case he sat on 115 committees, simultaneously.

No doubt the main reason Lord Desborough managed to get London to help him save the Olympics was only that everybody both liked him and appreciated his devoted efforts. The swain ideal of the English athlete at that time was non to concentrate on one sport (for goodness' sake, it's merely a bloody game), but if you do run a risk to succeed, appear to exercise so effortlessly (gentlemen practise not strain). With his rowing and swimming and fencing and lawn tennis, his Lordship was, as Gilbert and Sullivan might have had it, the very model of a mod English language Olympian. Empire magazine summed him up as "tall, well prepare up, a commanding presence, yet utterly devoid of airs or side, which ofttimes causes Englishmen to exist detested by the foreigner." Certainly (non different de Coubertin) it was his indomitable personality more than his charm that trumped. When the quick-witted Ettie had chosen Willie Grenfell over other younger, more socially eligible rivals, her cousin observed: "He may exist a little dull, just afterward all, what a comfort information technology is to be cleverer than ane'southward husband."

On Lord Desborough pressed. His most magnificent accomplishment was the construction of the Olympic stadium in Shepherd's Bush-league. From scratch, he raised the funds, and, for £220,000, had a 68,000-seat horseshoe ready for track, cycling, swimming, gymnastics and sundry other events in barely a twelvemonth and a half's time. And then, on July 13, 1908, before a packed house, more than 2,000 athletes of 22 nations marched—and athletes marched in file, then, "formed up in sections of four," optics correct—past Rex Edward, dipping their flags before the world's grandest monarch in what was just chosen the Smashing Stadium. All else had been prelude Just now had the modernistic Olympics truly begun.

Medals were presented for the first time. All measurements (except for the marathon) were fabricated metric. Regulations for all entrants—and all, past god, true-blue amateurs—were strictly defined. Even the first Winter Olympics were held late in October. The Businesswoman de Coubertin's buttons outburst. Stealing the words from an American clergyman, he fabricated the sappy declaration—"The importance of the Olympiads lies non and so much in winning equally in taking office"—that has evermore been trumpeted as the existent meaning of the movement, even if nobody this side of the Jamaican bobsled squad really believes it.

There was, however, one pasty wicket: The British forced the Irish to exist part of their team. Since there were a great many Irish-Americans on the U.South. team, some Yanks came over carrying a scrap on their shoulder for their cousins from the ould sod. Anglo-American relations were farther aggravated because a prickly Irish-American named James Sullivan had been appointed by President Roosevelt equally special commissioner to the Olympics, and Sullivan was convinced that the referees, who were all British, must be homers. Then, for the opening ceremony, someone noticed that of all the nations competing, two flags were non flying over the Bully Stadium—and wouldn't y'all know it? I of the missing standards was the Stars and Stripes.

(The other was Sweden's, and the Swedes were even more put out, just never heed.)

Sullivan, who could be a existent jerk—four years later, he distinguished himself before the Stockholm Games by unilaterally refusing to let any female Americans swim or dive considering he idea the bathing outfits too provocative—went out of his way to protest something or other every day. He started off, for instance, past claiming that the victorious English tug-of-war team wore illegal shoes. And then forth. For their part, the British grew increasingly irritated at the American fans, whose raucous cheers were hysterically described as "brutal cries."

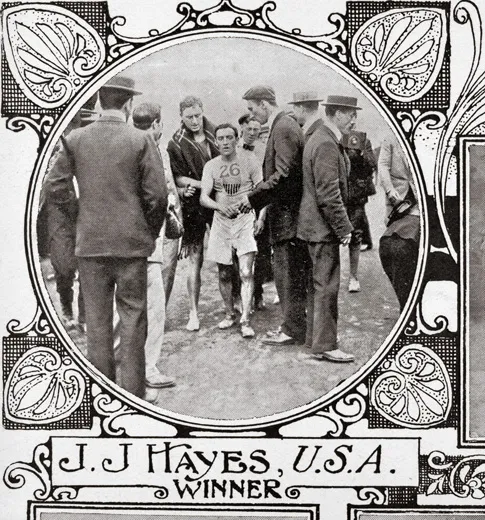

Controversy continued to ensue, invariably somehow involving Americans. The '08 marathon, for example, does surely even so boast the most botched-upwardly finish in Olympic register. Now, at the first modern Olympics, the marathon, starting in the real namesake town of Marathon, had been run into Athens for 24.85 miles, but at the London Games the altitude was diffuse to 26 miles 385 yards, which it remains, officially, to this day. The reason for this curious distance was that the race was started at Windsor Castle, so that Queen Alexandra's grandchildren would take the best vantage.

It was an exceptionally hot, steamy day, but the largest crowd always to see an athletic event in the history of humankind lined the streets. And hither came petty Dorando Pietri, a candy maker from Capri, downwardly through Shepherd's Bush-league, first into the Cracking Stadium, where the huge throng awaited. Unfortunately, equally the Times of London described it: "A tired man, dazed, bewildered, hardly conscious...his hair white with grit, staggered on to the track." Pietri not only would fall, but twice turned in the wrong direction, and just made information technology through those terminal 385 yards because, in a convoy of suits, helpful British officials held him up and escorted him dwelling.

Naturally, upon review, Pietri was disqualified. Notwithstanding, sympathy for the little fellow knew no bounds. The queen herself presented him with a special loving cup, hastily, lovingly inscribed. Not merely that, but, sure plenty, the runner who showtime made it to the terminate on his own and thus was fairly awarded the aureate past default, turned out to be an American of Irish gaelic stock. He had a nervus. You see, during these Games the British themselves took all the gold medals in boxing, rowing, sailing and tennis, and also won at polo, water polo, field hockey and soccer (non to mention their disputed-shoe-shod triumph at the tug-of-war), but the Yanks had dominated on the track, and thus information technology was deemed bad course for the barbarous Americans to revel in their homo'south victory over the dauntless little Italian.

Just that brouhaha could not hold a candle to the 400-meter concluding, when iii Americans went up confronting the favorite, Britain's greatest runner, a Scottish Ground forces officer named Wyndham Halswelle. Downward the stretch, i of the Americans, J. C. Carpenter, clearly elbowed Halswelle, forcing him out to the very border of the cinders. Properly, the British umpire disqualified Carpenter and ordered the race rerun.

Led by the obstreperous Sullivan, the Americans protested, lamely, and and so, in high dudgeon, also ordered the other 2 U.S. runners not to enter the rerun. Halswelle himself was so disillusioned that he didn't want to run either, but was instructed to, and, good soldier that he was, he won in what is still the only walkover in Olympic history. It left such a biting sense of taste in his mouth, though, that he raced but once more in his life, that only for a farewell turn in Glasgow.

Nevertheless all the rancor, Lord Desborough's '08 Games absolutely did restore de Coubertin's Olympics, establishing them as a healthy, going business organisation. Still, simple success as a mere sports spectacular is never plenty for Olympic pooh-bahs, and Lord Desborough felt obliged to bloviate: "In the Games of London were assembled some two m young men... representative of the generation into whose hands the destinies of most of the nations of the earth are passing....Nosotros hope that their meeting...may have a benign issue hereafter on the cause of international peace."

Only, of class, merely six years after the Olympic flame was extinguished, the world vicious into the well-nigh ghastly maelstrom of killing that any generation had always suffered. Hardly had the Great State of war started, at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, when Capt. Wyndham Halswelle of the Highland Light Infantry wrote in his diary how his men had bravely moved up the forepart a full fifteen yards against the Germans. This minute proceeds of footing came at the loss of life to 79 men. Three days later the captain was winged by a sniper, only, later the wound was dressed, he returned to his position. This time, the very same sniper shot him dead in the head. He was 32.

2 months on, Lord Desborough's eldest son, Julian Grenfell, a poet, brutal about Ypres, to be buried close past, with so many others, on a hill above Boulogne. A few weeks later that, not far away, His Lordship's second son, Billy, was so drilled with machine-gun bullets that his trunk was rendered remnants and merely left, like so many others, to spoil upon the battlefield. Nobody ever learned the lesson of how ephemeral the Games are improve than did Lord Desborough, he who made them forever possible.

London's get-go Olympics also left united states of america with the huffy reverberations of a celebrated incident, which is still, a whole century later, proudly cited past Americans. Unfortunately, it really only kinda, sorta happened. All right, though, first the glorious legend:

During the opening ceremony, as the American contingent passed the purple box, the U.Due south. flag bearer, a shot-putter named Ralph Rose, standing up for his Irish forebears, acting with noble premeditation, did non dip the Stars and Stripes before King Edward equally every other nation'south flagman did. Afterward, a teammate of Rose'southward named Martin Sheridan sneered: "This flag dips to no earthly king." And thereafter, at all subsequent Olympics, while all other countries go on to dutifully dip their national standard equally they pass the official box, our flag alone forever waves every bit high at the Olympics as the one Francis Scott Key saw by the dawn's early low-cal.

Well, equally sure as George Washington cut downwardly the cherry tree, it's a skilful all-American story. However, comprehensive research by Bill Mallon and Ian Buchanan, published in the Journal of Olympic History in 1999, casts doubt on nearly of the slap-up patriotic flag tale. Yes, Ralph Rose carried the flag, and while at that place were not 1, but two occasions when flag bearers were supposed to "salute," he surely simply dipped information technology once—although when asked about it, he denied that anyone had suggested he forgo protocol to brand a political point. For all nosotros know, Rose may have but forgotten to drop the flag. Martin Sheridan'southward famously jingoistic remark about how the ruddy-white-and-blue "dips to no earthly king" did not appear in print until virtually 50 years subsequently—long after Sheridan was dead.

Moreover, at the time, the episode didn't even rising to the level of a storm in a teapot. Mallon and Buchanan could not observe a single reference in the British press to Rose's allegedly insulting activeness, and the New York Herald even went out of its way to write that the crowd's cheers for the U.South. contingent were "peculiarly enthusiastic." Rose's activeness set up no precedent either. In subsequent Olympics, the flag was non lowered on some occasions—most assuredly not before Adolf Hitler in 1936—but it was politely dropped downwards on others. Moreover, at various times, other nations have also called not to dip.

In 1942, rendering Olympic flag-dipping moot, Congress passed a police force that declared "the flag should not be dipped to whatsoever person or thing." That seems terribly overwrought, just it was in the midst of Globe War II. Ironically, so, Mallon and Buchanan concluded that the last U.S. Olympian known to take dipped the flag was Billy Fiske, a two-time bobsled gilt medalist, who lowered the standard at Lake Placid, New York, in 1932 before the American official who opened the Winter Games, the governor of New York, one Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Coincidentally, Fiske himself is surely more identified with England than any other American Olympian in history. He was born in Brooklyn, but his forebears were English, from Suffolk. He had won his outset gold, driving the bobsled, in 1928 at St. Moritz when he was just xvi, and then he matriculated at Cambridge, where he read economics and history before coming back to usa to repeat his victory in the '32 Games, when he too proudly dipped the flag earlier FDR.

But Billy Fiske would return again to England.

As the Olympic Motility wants to think that it succors peace and goodwill, so too is it reluctant to acknowledge that even in the Games, bad people upward to no skilful do still muck most. If yous're for the Olympics, null much else matters. When the Japanese government reluctantly had to give up the 1940 Games because it was otherwise occupied with killing and raping Chinese, the International Olympic Committee but decreed that the Wintertime Games would be returned to Deutschland, because they'd been so bang-up at that place in '36. This decision was fabricated in June of 1939, only three months earlier the Nazis invaded Poland.

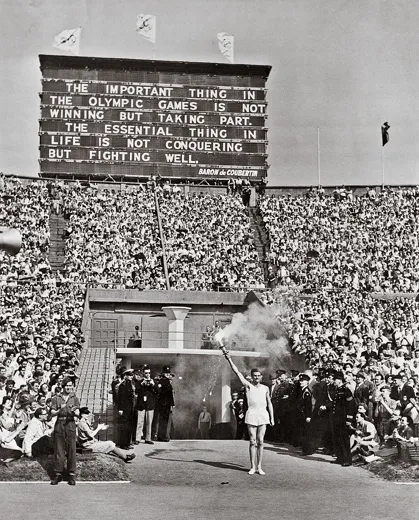

Later on the unfortunate hostilities were ended, the IOC still embraced Nazi and Fascist members. "These are erstwhile friends whom we receive today," the president, a Swede named Sigfrid Edstrom, noted later. And because the prove must go on as if nil was awry, poor London was the platonic symbolic choice. Information technology was September 1946 when the decision was hurriedly made—again, giving the hosts barely a year and a half to prepare. Non everyone was on board, either. "A people which...is preparing for a winter boxing for survival," the Evening Standard editorialized, "may exist forgiven for thinking that a full yr of expensive preparation for the reception of an army of foreign athletes verges on the border of excessive."

London in the peace of 1946 was barely amend off than during the state of war. Never mind that much of it nonetheless lay, bombed, in rubble. Citizens were allotted but 2,600 calories per twenty-four hour period. All sorts of foods were still rationed; indeed, staff of life rationing wouldn't end till but days before the Olympics began. I recall Sir Roger Bannister, the kickoff 4-minute miler, telling me that, with no disrespect to Bob Mathias—the 17-yr-old American who won the decathlon in London—no English language athlete could have possibly enjoyed sufficient nutrition to allow him to attain such a feat at such a immature age.

Olympic village? Foreign athletes were warehoused in billet and college dormitories. British athletes lived at domicile or bivouacked with friends. The women were obliged to brand their own uniforms ("the leg measurement should be at to the lowest degree iv inches across the bottom when worn"). The men were generously issued two pairs of Y-front underpants ("for ease of movement")—they being a luxury particular invented in the '30s. The Austerity Games, they were chosen, and they were. At the opening ceremony, Kipling'south poem, "Not Nobis Domine," was selected to be sung by a huge choir (as the inevitable peace doves fluttered away)—the empire'south great troubadour reminding the assembled "How all too high we hold / That noise which men call Fame / The dross which men call Gold." The British were proud, but it wasn't time yet for showing off.

Luckier nations imported their own food. The U.S. team, for example, had flour flown over every 48 hours. The Yanks were shipped 5,000 sirloin steaks, 15,000 chocolate confined and other edible luxuries that Londoners rarely saw, let alone consumed. The Americans promised to hand over their leftovers to hospitals.

The Continent, of grade, was in no better shape than England. Hellenic republic, in particular, was in the midst of a civil state of war, which certainly did non stop for the Olympics. The Marshall Programme had just started in April. The Soviet Marriage was blockading Berlin. Not surprisingly, the just European nation that achieved much success was Sweden, which had remained comfortably neutral during the war. The well-fed Us, of course, utterly dominated the medal count, equally it did everything that counted in the world then.

But as London had saved the Olympics by taking the Games in '08, in '48, it took the Games on in an effort to save its own spirit. In a higher place all, King George wanted them. He hadn't wanted to be king, and and so he'd had nothing but war and impecuniousness to reign over. At least he would accept the Games. He only had a few more years to alive, too. Nineteen-forty-eight would be the best; not only the Olympics, just his eldest girl, Elizabeth, would deliver him his kickoff grandchild. And, equally a bonus: He who fought stuttering only needed to say this in public: "I proclaim open the Olympic Games of London, celebrating the fourteenth Olympiad of the modern era."

At least Wembley was intact. Dissimilar, say, Wimbledon, which had suffered bombing harm, the grand old stadium had never been striking. 3 major commercial sponsors volunteered to buttress the regime financing—Brylcreem, Guinness and Craven A—a hair gel, a brew and a smoke. Only at offset nobody seemed to intendance about the Olympics. There was no money to spruce upwardly the urban center and ticket sales lagged. Sports pages continued to pay more than attention to horses and dogs, racing. Foreigners were stupefied. Wrote the New York Times: "The British public interest in the games...has been slight, owing to the typical British aversion to advance publicity and American manner ballyhoo."

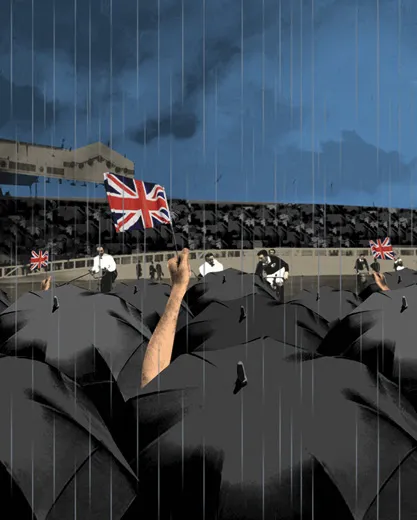

Only then, all suddenly, blighty: Just every bit a rut wave swept over the city, London came to life. For the opening day, it was 90 degrees, but 83,000 fans crushed upon Wembley. The muckety-muck members of the IOC showed up in their cutaways and pinnacle hats to greet the male monarch, himself resplendent in his Purple Navy compatible. Queen Elizabeth joined him in the royal box, merely Princess Elizabeth, five months on, stayed away from the heat. Princess Margaret beamed in her stead.

And almost every day, even when the rains returned, Wembley was filled. The attendance records fix past the Nazis in '36 were topped. Notwithstanding Kipling'due south admonition, dissonance and dross once once again prettily bloomed. In November, too, Princess Elizabeth gave to king and nation a son and heir.

This summer of 2012 the Games volition begin on July 8. Of course, now, these will be the ones at Much Wenlock. Just considering there'll be some rather larger Games, inaugurating the XXXth Olympiad, starting later on in the month, is no reason to telephone call off the older Olympics. As well, a footling scrap of Wenlock will exist part of the London Games, for one of the mascots is, in fact, named Wenlock. It is a hideous one-eyed animate being, the less described the meliorate. But it is the thought that counts. Penny Brookes would be well pleased.

The mascot Wenlock will exist cavorting on Friday, July 27, when the multitude of Olympic nations march in, passing earlier Queen Elizabeth. Some, if non almost all, will dip their flags to her, as they did to her father in '48, her groovy-granddad in '08, as Billy Fiske did to FDR in '32.

Fiske, the Cambridge old boy, returned to London in 1938 as a banker, marrying Rose Bingham, the former Countess of Warwick, at Maidenhead, in West Sussex. The next year, when England went to war, Fiske passed himself off every bit a Canadian, becoming the first American to join the Imperial Air Force. He was assigned to the base at Tangmere, not far from where he'd been married. His unit was No. 601 Auxiliary Air Forcefulness Squadron, and some of the more experienced pilots were initially dubious almost "this untried American adventurer." Fiske, the athlete, was a quick learner, though, and soon earned full marks, flight the lilliputian single-engine, hundred-gallon Hurricane. Full out, it could brand 335 miles an 60 minutes. Sir Archibald Hope, his squadron leader, came to believe that "unquestionably, Billy Fiske was the best pilot I've always known."

The summer of 1940 might accept climaxed with the Games of the XIIth Olympiad, simply instead information technology was the time of the Boxing of Britain, and on the afternoon of Baronial xvi, Pilot Officeholder Fiske's squadron was ordered out on patrol. Fiske went upward in Hurricane P3358. A flying of Junker Stukas, dive-bombers, came across the declension down by Portsmouth, the 601 engaged them, and, in a serial of brusque dogfights, shot downwardly eight of the Stukas.

Yet, a German gunner made a hit on Fiske'south fuel tank. Although his hands and ankles were badly burned, Fiske managed to bring P3358 back to Tangmere, gliding over a hedgerow, belly-landing between fresh bomb craters. He was pulled from the flames just earlier his Hurricane exploded, just he died two days after. At his funeral, he was laid in the ground nearby at Boxgrove, in the g of the ancient Priory Church. The RAF ring played, and, distinctively, his coffin was covered by both the Marriage Jack and the Stars and Stripes.

As Baton Fiske was the starting time American to join the RAF, so likewise was he the first American to die in the RAF.

The next July Fourth, Winston Churchill had a memorial tablet installed at St. Paul'southward Cathedral. It rests but a few steps away from Lord Nelson's sarcophagus, and it reads:

PILOT Officeholder WILLIAM MEADE LINDSAY FISKE III

Majestic AIR FORCE

AN AMERICAN Denizen

WHO DIED THAT ENGLAND MIGHT LIVE

18 Baronial 1940

It would be dainty if whoever carries the American flag by the royal box come up July 27—with a wink and a nod—dips the flag in honor of Billy Fiske, the one Olympian who binds the Usa and England. The law says you can't do that for whatsoever "person or affair," only it doesn't say anything about honoring a memory. And, should Queen Elizabeth think the dip is for her, fine, none need exist the wiser.

John Ritter's work has appeared in several major magazines.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-little-known-history-of-how-the-modern-olympics-got-their-start-138117709/

0 Response to "One Month Out of Every 48 Ritual When Did the Olypics Start Again"

Post a Comment